intro

intro

Our principal goal from the outset of this research was to explore new modes of engagement between musicians, architects and their respective audiences. Many parallels have been observed, documented, and explored between the two disciplines- whether artistic qualities, internal structures, even parallels in their evolution and standardization- but remarkably unexplored is the inherent exclusivity of the professional and academic qualities of both fields. Both require years of training, typically in institutional settings like this university, in order to engage with the disciplines.

Among many aspects of this disciplinary barrier, is the codified language of our physical instruction manuals. We lock information away in these documents- scores and construction documents. While these critical pieces of dispatch are understood by architects and musicians, who have spent years gaining familiarity with their symbols, nomenclature, and conventions, they are inaccessible to those without formal training.

Through a series of exercises and studies, we have spent the past months breaking down these forms of visual communication and re-representing them in formats and visualizations that don’t rely on disciplinary knowledge. Working back and forth between the disciplines, these realizations are working towards a shared language between music and architecture that can convey qualities of both fields in more accessible formats without oversimplification.

Among many aspects of this disciplinary barrier, is the codified language of our physical instruction manuals. We lock information away in these documents- scores and construction documents. While these critical pieces of dispatch are understood by architects and musicians, who have spent years gaining familiarity with their symbols, nomenclature, and conventions, they are inaccessible to those without formal training.

Through a series of exercises and studies, we have spent the past months breaking down these forms of visual communication and re-representing them in formats and visualizations that don’t rely on disciplinary knowledge. Working back and forth between the disciplines, these realizations are working towards a shared language between music and architecture that can convey qualities of both fields in more accessible formats without oversimplification.

precedents

plan of st. gall, reichenau, ca.820-830

To begin our research, we sought to find precedents for our research - both in the histories of architecture and music and previous moments in which they intersected. We began by looking at the emergence of documentation in each field. The earliest known architectural drawings are etchings on stone from around 2000BC; the oldest surviving document, however, is the ninth-century plan of St. Gall, a monastic compound in what is now Switzerland.

guidonian

hand from late 15th century manuscript,

guidonian

hand from late 15th century manuscript,oxford university ms canon. liturg. 216. f.168 recto

In music, the first notation using language to describe music emerged around 1400BC. By 600BC, symbols-based notation systems had begun to emerge. Of particular interest to us was the Guidonian Hand, a mnemonic device from the Middle Ages - invented by Italian music theorist Guido of Arezzo - in which different locations on the hand represented a specific pitch. We were interested by the unique intersection of physical representation and symbology in this notational system.

Dry Landscape at

Ryōan-ji

Dry Landscape at

Ryōan-ji

In more recent history, however, there have been more examples of interdisciplinary influence between music and architecture. Among these, one that we found the most interesting was John Cage’s Ryoanji. This piece is named after the Kyoto, Japan rock garden of the same name.

For this piece, Cage made prints tracing 15 different stones in the garden; the performers are instructed to interpret these curves as the contour of their line, played as glissandi within the range of their instruments. In this piece, then, an architectural work is the direct inspiration for musical material. These drawings - representations of physical objects - are repurposed as a form of notation.

listen

For this piece, Cage made prints tracing 15 different stones in the garden; the performers are instructed to interpret these curves as the contour of their line, played as glissandi within the range of their instruments. In this piece, then, an architectural work is the direct inspiration for musical material. These drawings - representations of physical objects - are repurposed as a form of notation.

listen

An excerpt from Ryonaji, a composition by John Cage1

Image by Marina Levatskaya from The Force of Things 2017 performance with the International Contemporary Ensemble

Image by Marina Levatskaya from The Force of Things 2017 performance with the International Contemporary Ensemble

We also discussed a more recent piece - The Force of Things, a collaboration between Ashley Fure, a composer, and Adam Fure, an architect. Premiered in 2016, this work is an immersive experience in which audience members enter into a space of scultped matter and collected objects. Speakers within this space emit sounds too low for humans to hear, but that cause these materials to resonate. In this piece, like the Cage, a sonic experience is dicatated in large part by an architectural phenomenon - much of the musical material is the result of resonant objects. However, in this immersive experience, the physical space itself is activated by sonic material - the low frequencies coming from the speakers. In this way, sound and space enter a reciprocal relationship - each element of the installation making the other possible.

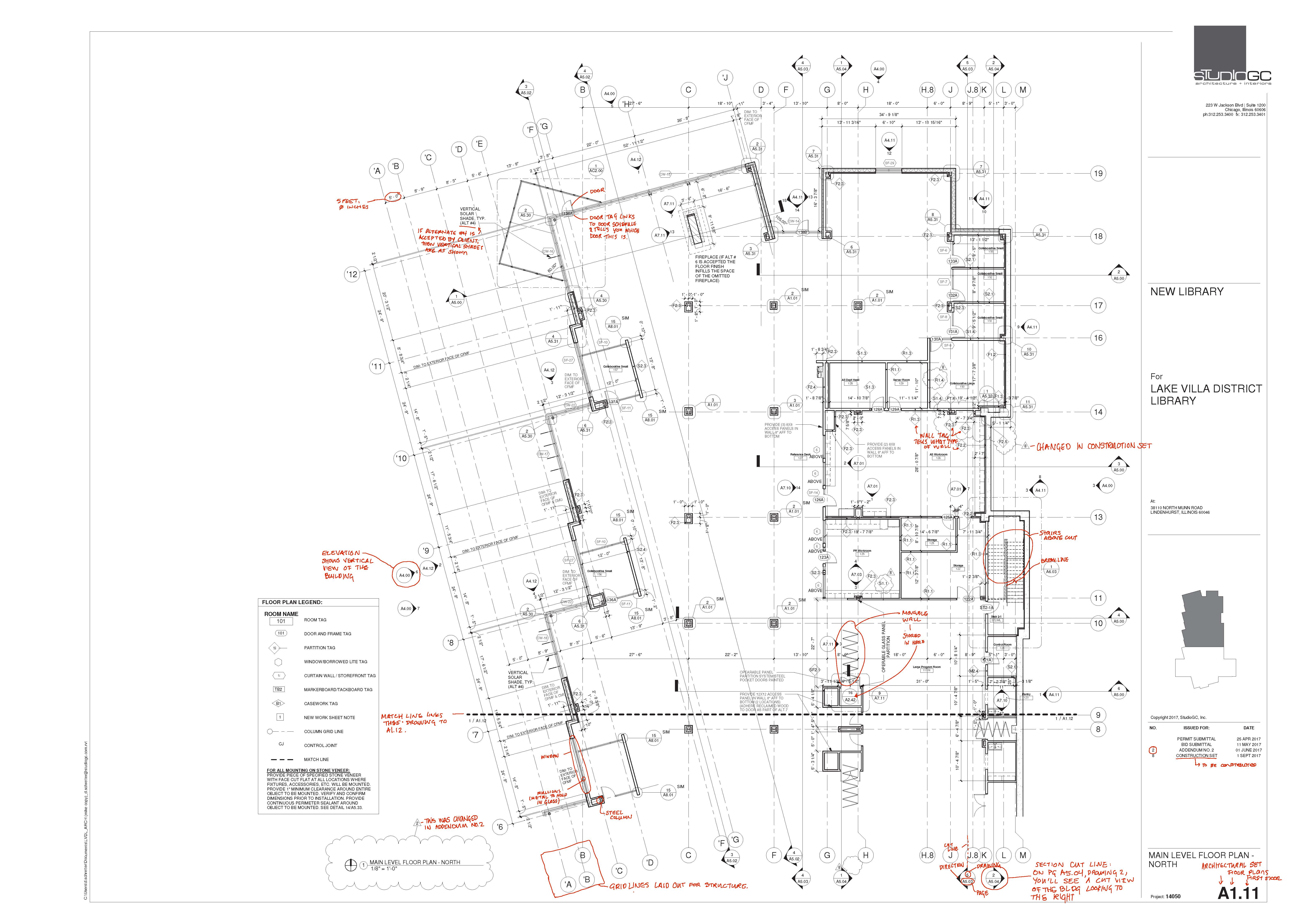

score and plan markup

Recognizing that music scores and construction documents contain layers of codified information, we began our research with an exercise designed to get each of us thinking about the particulars and extents of these disciplinary languages. Our task was to annotate the documents as though we were describing them to someone outside either discipline, meaning every symbol, all nomenclature, and ideas had to be explained in detail. In addition, we also annotated a document from the other discipline, each of us with varying levels of familiarity.

We chose not to collaborate on a strategy or approach. The purpose of this exercise was more anecdotal than rigorous, intended to be an entry point into the many questions we had discussed in forming our research nexus. We were trying to eek out strategies for translation.

We chose not to collaborate on a strategy or approach. The purpose of this exercise was more anecdotal than rigorous, intended to be an entry point into the many questions we had discussed in forming our research nexus. We were trying to eek out strategies for translation.

Dichterliebe, Op. 48 by Robert Schumann2

copyright StudioGC architecture+interiors, 20213,4

After gathering the three versions of the document together, we began discussing our experiences with the task. As a group, we each noted the difficulty in getting started; questions of hierarchy emerged. What are the most important, essential annotations? What are the frameworks these documents operate within, more broadly? How much of this context is essential just to read the document?

We identified two underlying approaches to our annotations; global and local.

The Global Approach focuses more on describing the logic and organization of symbols, rather than their specific function in the documents we annotated. Overall, this strategy is about providing the recipient with a general toolkit to be able to approach any score or construction document and break it down into general parts. The value here is that it prepares a recipient to engage with every document on some level, but would be insufficient to actually serve as a translation for a specific document.

The Local Approach dives into the specific meaning of each symbol in its context, ignoring the general logics at work. These annotations provide translations about the way symbols are applied in the document, and what they tell the reader in a particular context. While this strategy works as a one-off translation of a specific document, it does not necessarily help the reader understand other documents in each discipline.

This p is a dynamic marking, describing the loudness and softness of the notes.

The lower right corner of a drawing will usually provide a scale, used to measure a drawing on paper and translate it to full sized dimensions.

The lower right corner of a drawing will usually provide a scale, used to measure a drawing on paper and translate it to full sized dimensions.

This p means piano, or play the notes here softly.

This drawing is at ¼” = 1’ scale, so ¼” on paper represents 1’ in real space

This drawing is at ¼” = 1’ scale, so ¼” on paper represents 1’ in real space

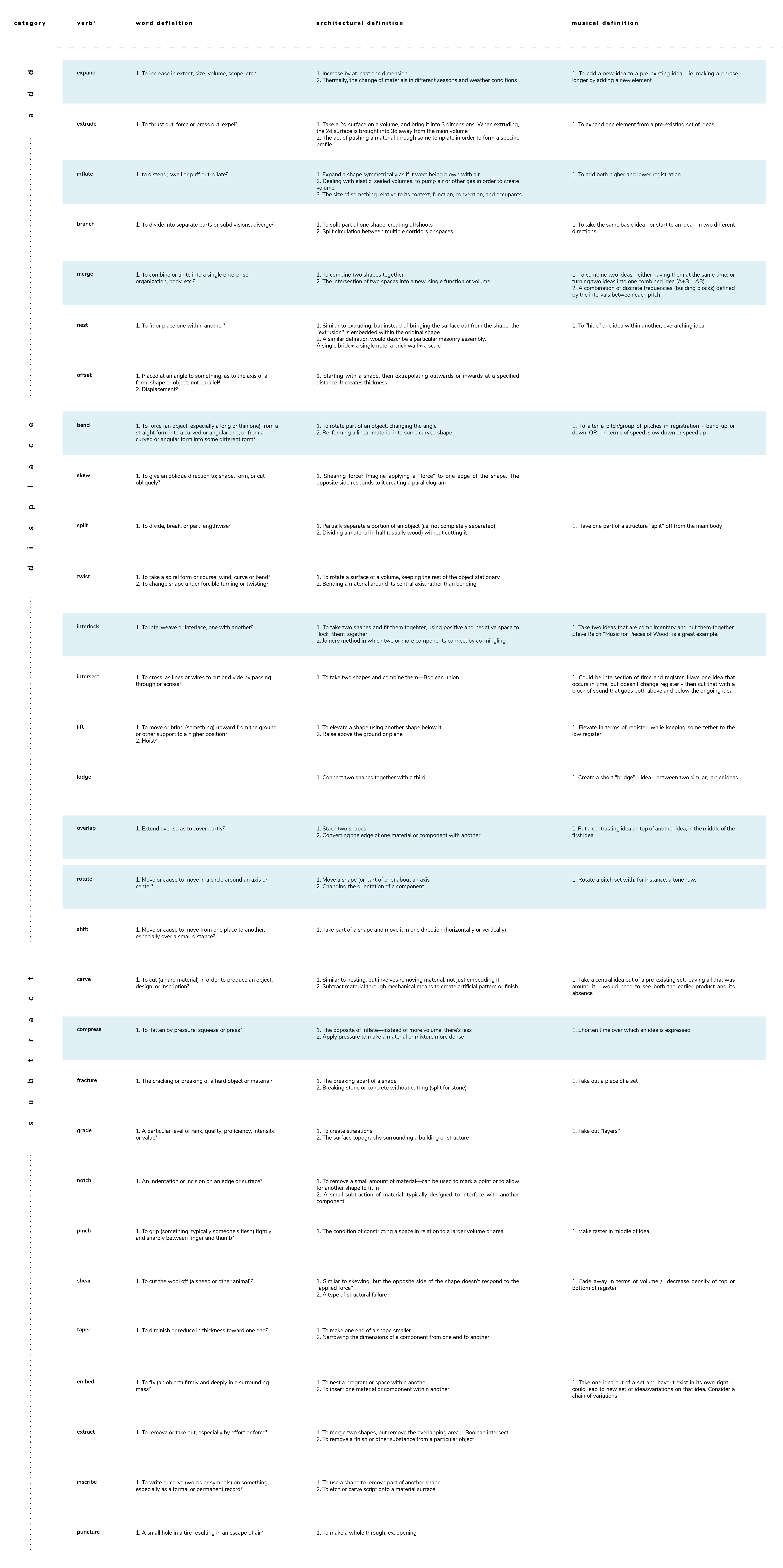

We also generated a taxonomy to organize musical and architectural symbols based on their respective use.

definitions + words

operative design: a catalog of spatial verbs

by anthony di mari and nora yoo

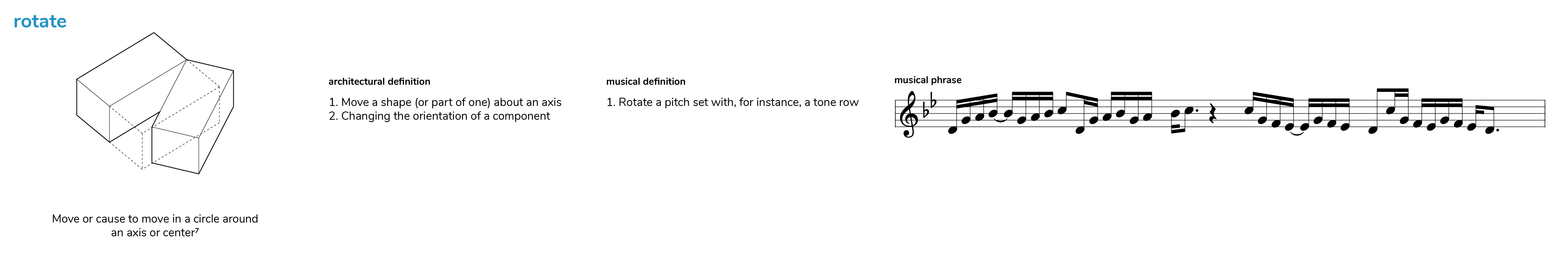

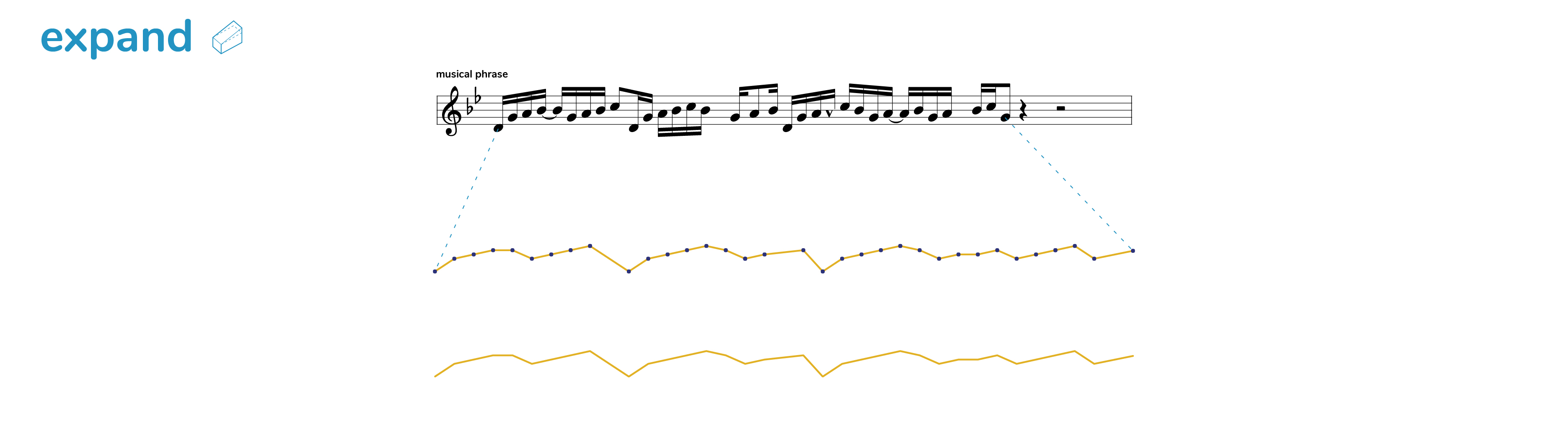

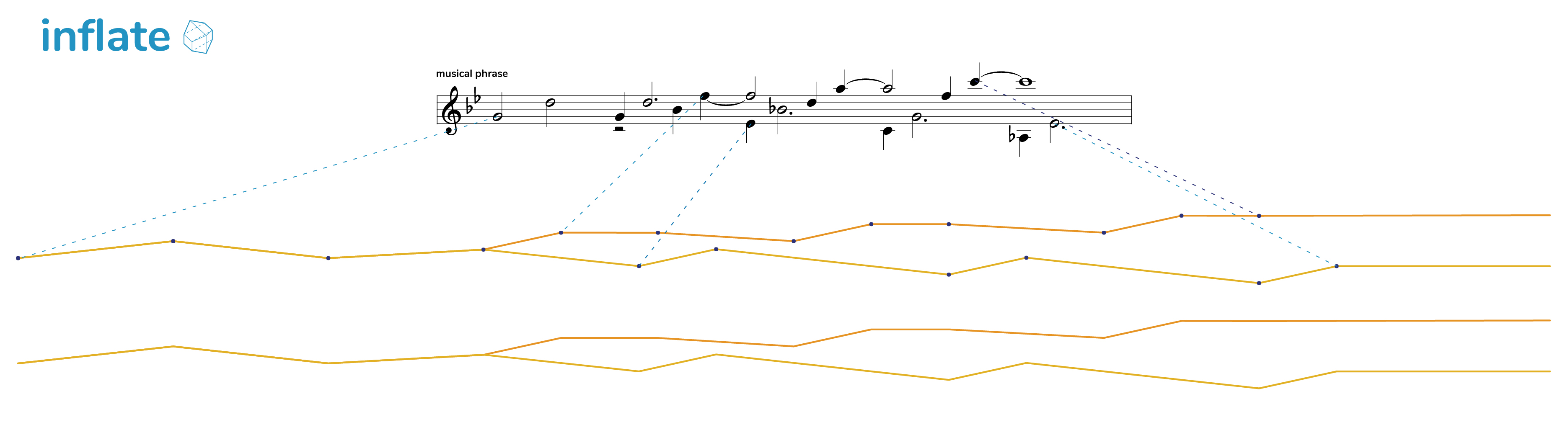

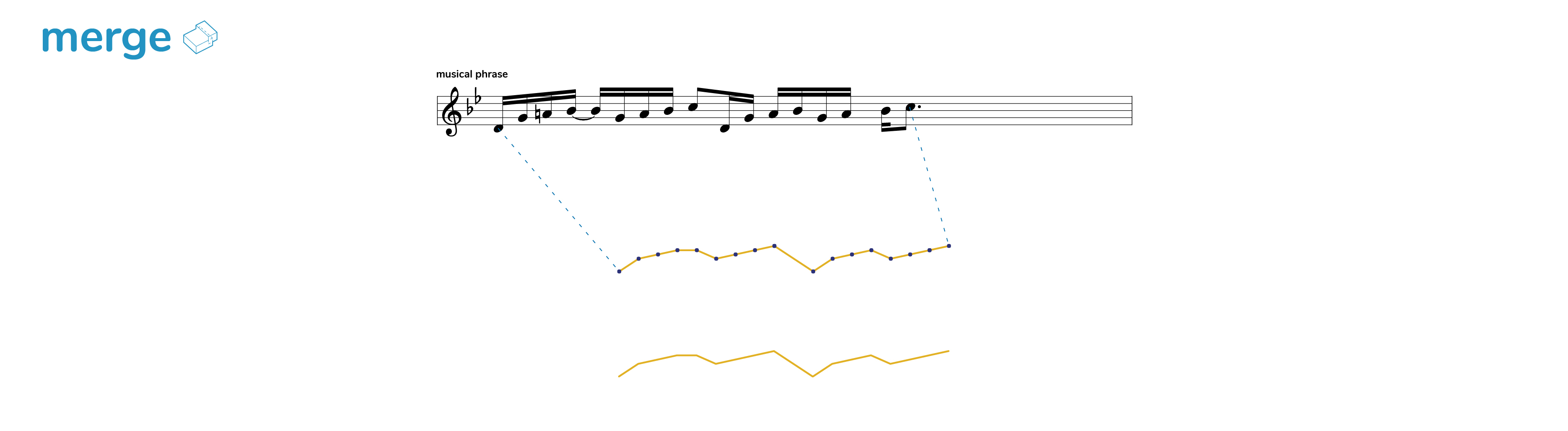

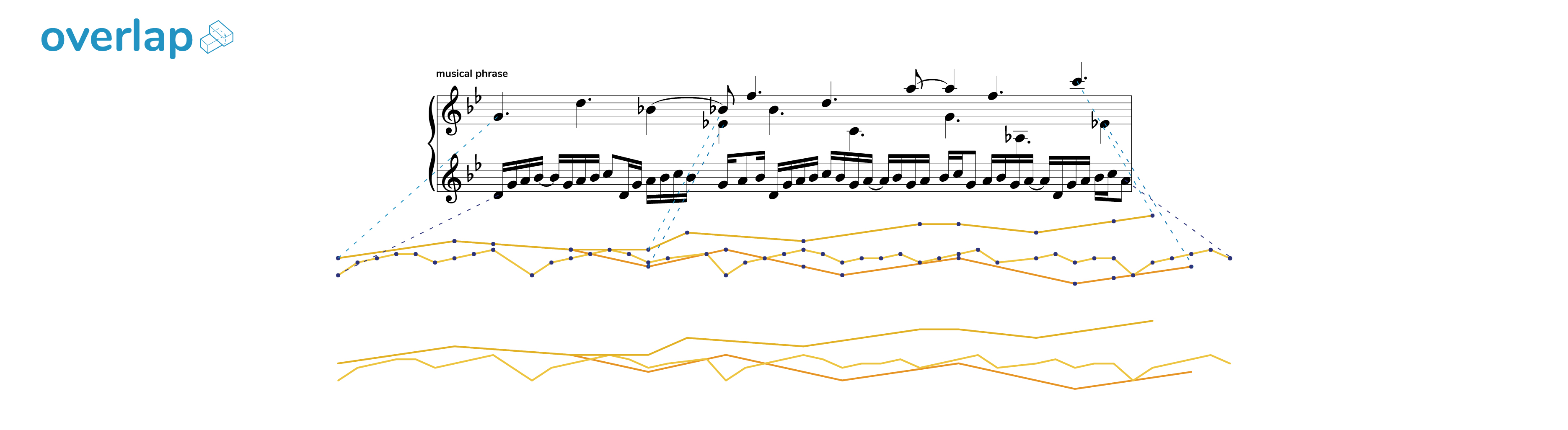

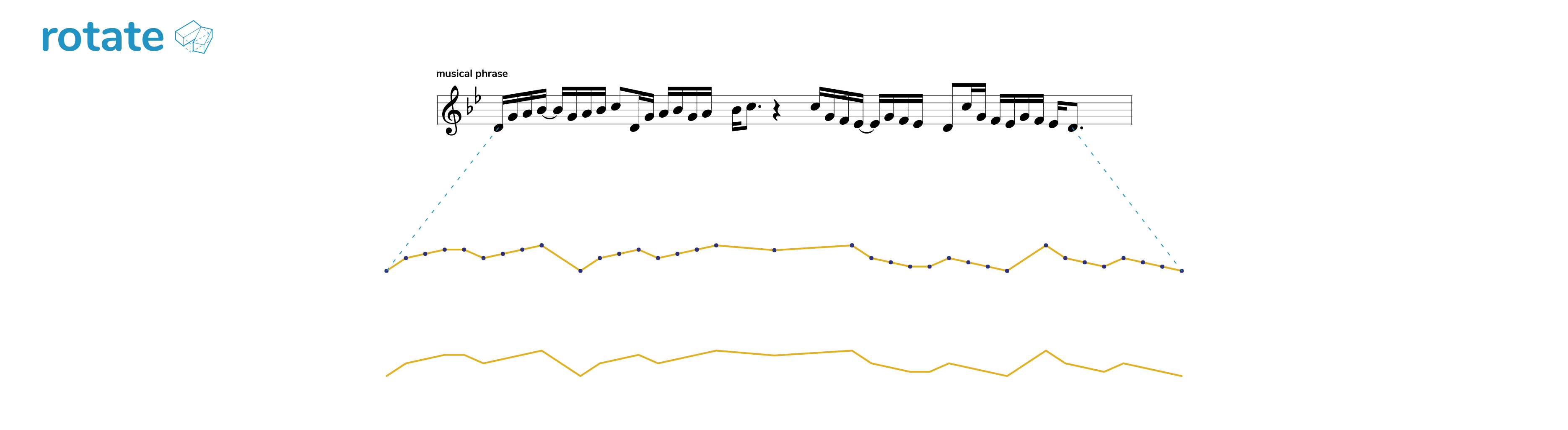

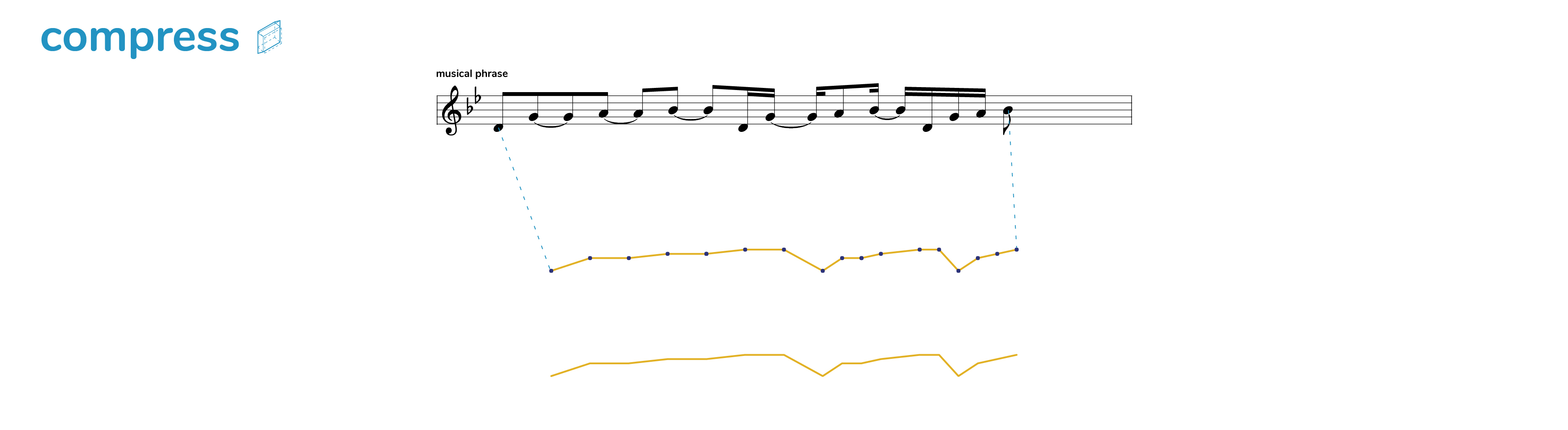

Our next step was to provide a disciplinary-specific definitions for verbs from Anthony Di Mari and Nora Yoo’s Operative Design: A Catalogue of Spatial Verbs. We began by examining each word as a from a non-disciplinary framework. Then, Kaylee and Tyler thought about how the verb could be explained spatially. Referring to the drawn diagrams and potential examples helped. Leonard translated Di Mari and Yoo’s spatial verbs into a musical verbs by imagining what each verb might suggest in a musical context.

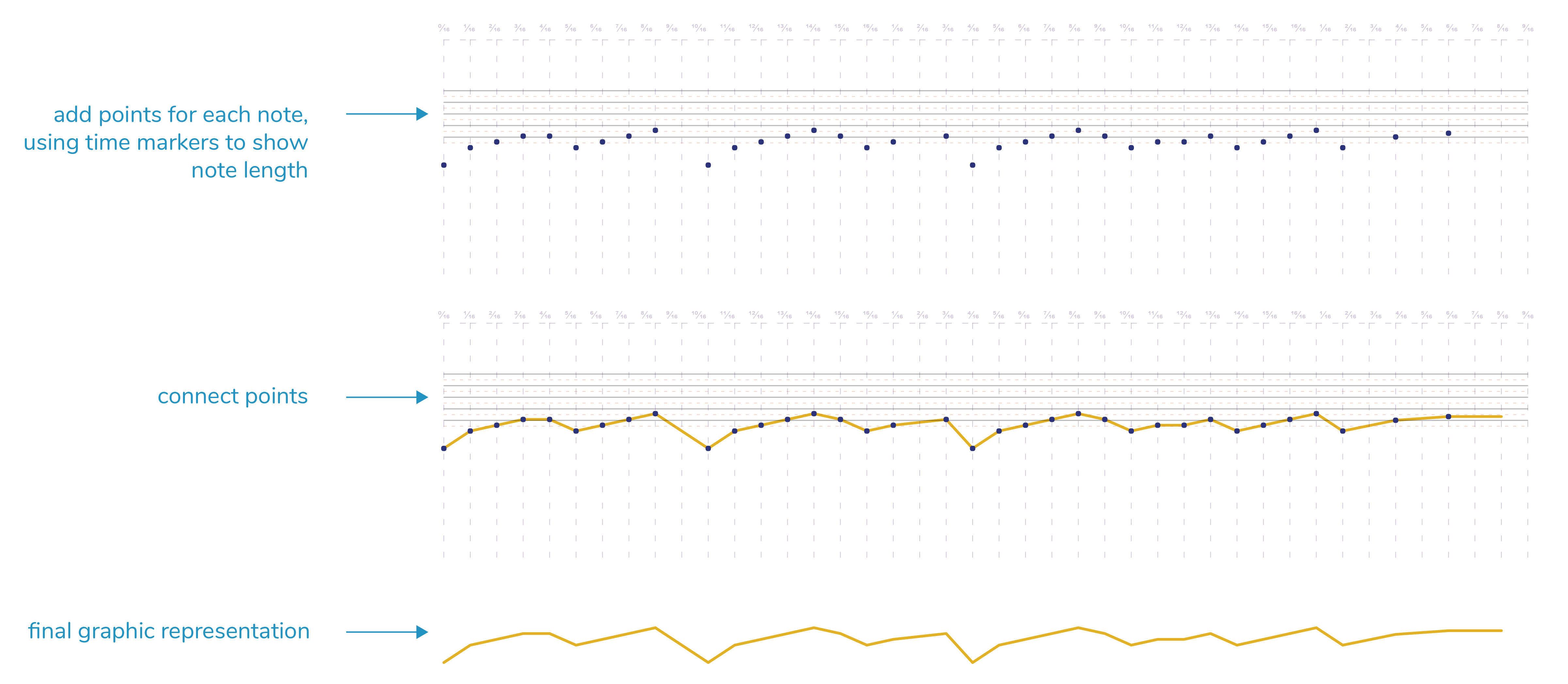

musical phrases + graphical representation

Because these translations were quite subjective, we often found

multiple definitions that fit the same word. Translating the three dimensionality of the spatial diagrams to two

dimensional musical ideas proved difficult. We also found that the musical ideas were difficult to describe as words. This led us to our next step; Leonard sketching out muscial ideas for a subset of these verbs.

Each of these translations worked from a common musical motif - a diatonic and mostly step-wise pattern in the key of G minor - and manipulated the motif according to the musical definition of the spatial verb. This occured in the same way that di Mari and Yoo used the extruded rectangle in their diagrams-- each was manipulated by the spatial verbs.

Most of the phrases entailed straightforward alterations or extensions of this initial motif - playing with length and rhythm, for instance. In others, Leonard added a second voice to illustrate the verb. In expand, for example, two voices move apart - one ascending, the other descending - in a series of fifths; in interlock, a second voice repeats the exact pattern of the first, offset by a half a beat, such that the voices, indeed, interlock.

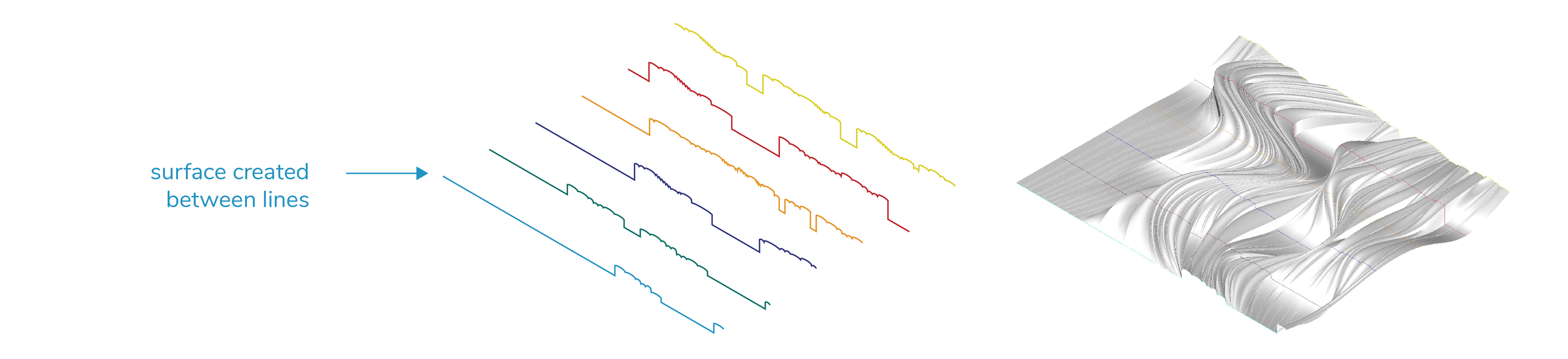

To bring this sonic realization back into the spatial realm, Kaylee and Tyler began devising techniques for translating them into a spatial form.

Most of the phrases entailed straightforward alterations or extensions of this initial motif - playing with length and rhythm, for instance. In others, Leonard added a second voice to illustrate the verb. In expand, for example, two voices move apart - one ascending, the other descending - in a series of fifths; in interlock, a second voice repeats the exact pattern of the first, offset by a half a beat, such that the voices, indeed, interlock.

To bring this sonic realization back into the spatial realm, Kaylee and Tyler began devising techniques for translating them into a spatial form.

expand

This method does a good job of showing large trends within a composition.

For example, in Bend, this method can illustrate how the two (musical) lines converge and diverge. In Interlock, overlapping the two (musical) lines revealed staggered (graphical) lines that corresponded with the round that Leonard wrote.

graphical representation + musical interpretation

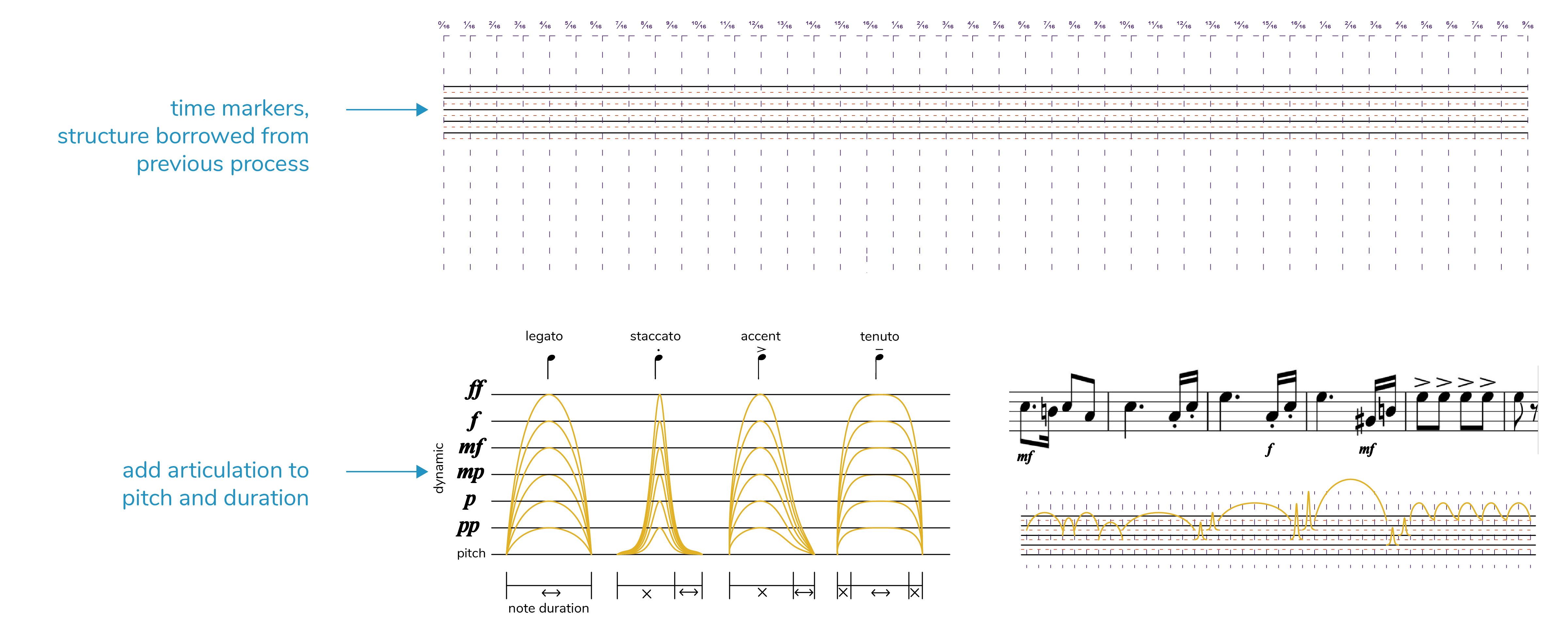

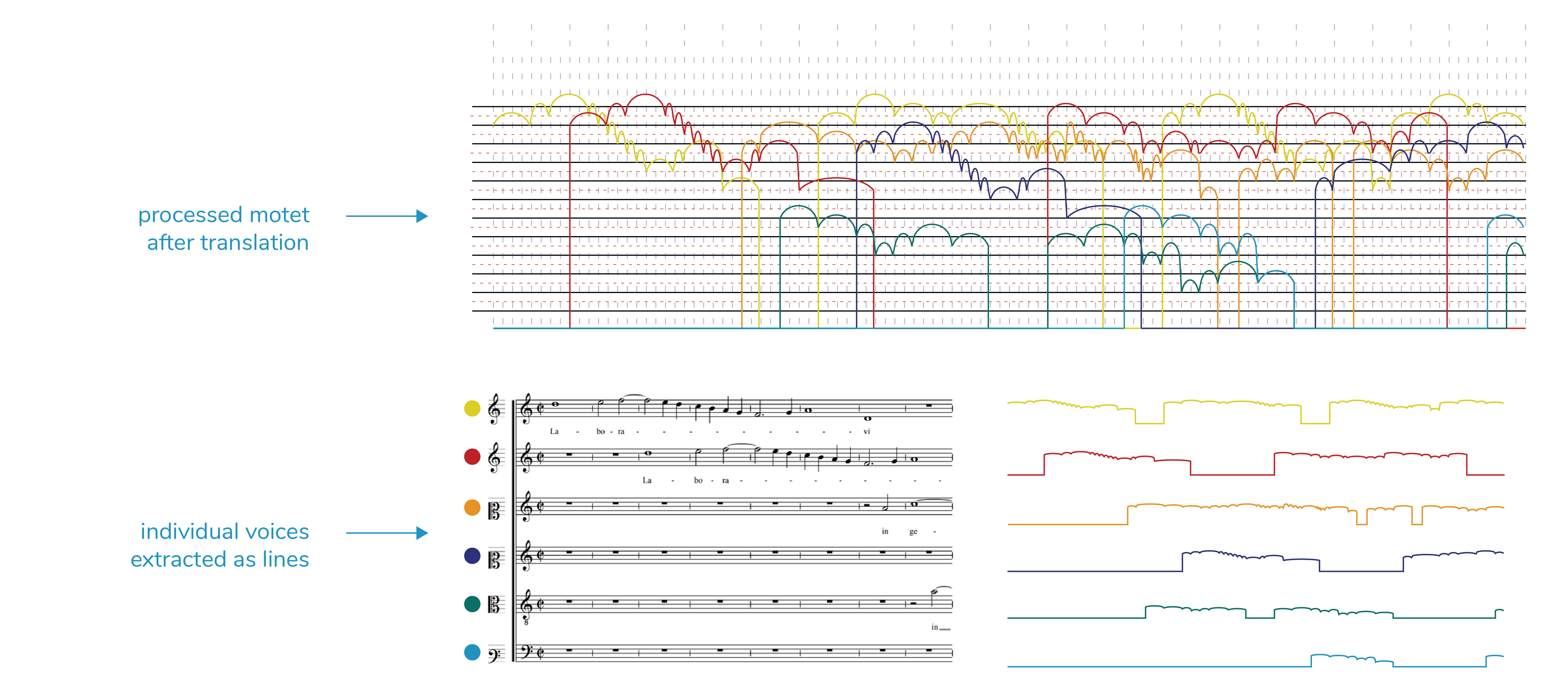

For our final exercise, we experimented with the process of translating between media at a larger scale. Leonard suggested looking at a motet by sixteenth-century English composer Thomas Morely titled Laboravi in gemitu. Leonard suggested this widely-known six-part motet because of its construction on a basic motif - a three-note ascending pattern that appears in each voice throughout the piece. This motif could be considered the basic “building block” of the piece.

Leonard then created a sonic representation of Tyler’s model - effectively trying to read the physical realization musically, as Tyler had aimed to interpret musical notation visually. There was one important element, however: Leonard was concious not to work from the original motet, but from Tyler’s model. Leonard’s interpretation - an electronic composition - attempted to follow the contours of Tyler’s model. Leonard interpreted the y-axis of Tyler’s diagram as pitch and the x-axis as time, with each new voice entering at a higher pitch. Where the contour lines grew closer together, so did the pitches; where they grew more distant from each other, the pitches expanded in repertoire.

We were interested here in a process of re-translation - how a dialogue between these two mediums could lead to evolving meanings and interpretations rather than stasis. What we ultimately found is that the final product - a sonic realization of a visual model - differed dramatically from the original inspiration behind the model. Most profoundly, however, this exercise speaks to the subjectivity with which people in either field - and people in general - interpret both sonic and spatial notation and materials.

We were interested here in a process of re-translation - how a dialogue between these two mediums could lead to evolving meanings and interpretations rather than stasis. What we ultimately found is that the final product - a sonic realization of a visual model - differed dramatically from the original inspiration behind the model. Most profoundly, however, this exercise speaks to the subjectivity with which people in either field - and people in general - interpret both sonic and spatial notation and materials.

sources

1. John Cage, Ryoanji (New York: Henmar Press, 1984), 2.

2. Robert Schumann, Dichterliebe Op. 48 (Leipzig: C.F. Peters, n.d.), 106.

3. StudioGC, Lake Villa District Library, Main Level Plan, North (Sheet A1.11 with annotations), 2017.

4. StudioGC, Lake Villa District Library, Main Level Plan, South (Sheet A1.12 with annotations), 2017.

5. Thomas Morely, Laboravi in gemitu ed. Daniel van Gilst (Oxford: Bodleian Library, Mus. MS f1.1-6),

6. Di Mari, Anthony, Nora Yoo. 2018. Operative Design : A Catalogue of Spatial Verbs. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: BIS Publishers.

7. “Dictionary by Merriam-Webster: America’s Most-Trusted Online Dictionary.” n.d. Accessed August 3, 2020. https://www.merriam-webster.com/.

8. “Dictionary.com Is The World’s Favorite Online Dictionary.” n.d. Dictionary.com. Accessed August 3, 2020. https://www.dictionary.com/.

2. Robert Schumann, Dichterliebe Op. 48 (Leipzig: C.F. Peters, n.d.), 106.

3. StudioGC, Lake Villa District Library, Main Level Plan, North (Sheet A1.11 with annotations), 2017.

4. StudioGC, Lake Villa District Library, Main Level Plan, South (Sheet A1.12 with annotations), 2017.

5. Thomas Morely, Laboravi in gemitu ed. Daniel van Gilst (Oxford: Bodleian Library, Mus. MS f1.1-6),

6. Di Mari, Anthony, Nora Yoo. 2018. Operative Design : A Catalogue of Spatial Verbs. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: BIS Publishers.

7. “Dictionary by Merriam-Webster: America’s Most-Trusted Online Dictionary.” n.d. Accessed August 3, 2020. https://www.merriam-webster.com/.

8. “Dictionary.com Is The World’s Favorite Online Dictionary.” n.d. Dictionary.com. Accessed August 3, 2020. https://www.dictionary.com/.

presentations

“Music, Architecture, and the Spatialization of Sound.” Presented at the Architecture Student Research Grant (ASRG) Project Presentations, January 27, 2021.